|

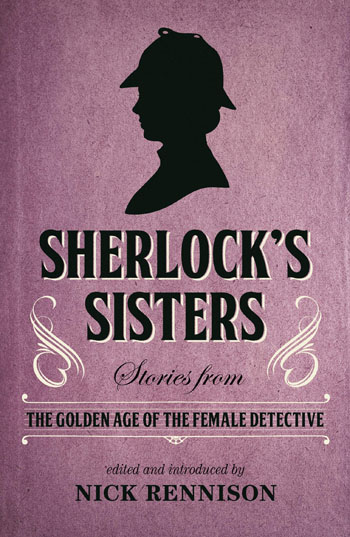

SHERLOCK’S SISTERS : STORIES FROM THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE FEMALE DETECTIVE

Edited and introduced by Nick Rennison

No Exit Press. 319

pages. £9.99. ISBN 978-0-85730-398-1

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Reviewing an earlier anthology edited by Nick Rennison (More

Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, NRB, June 2019), I pointed to the

context in which the stories had originally appeared in print.

The late-Victorian and Edwardian periods saw a wide range of

magazines and newspapers on sale. They were largely aimed at an

audience which didn’t want highbrow literature and erudite essays.

Entertainment, whether in the form of lively factual articles or

popular fiction, was what the editors looked for on the whole. The

number of magazines competing for attention on a regular basis meant

that they weren’t all likely to be successful.

Publications came and went. But there was a demand for

material and writers could earn a reasonable income if they came up

with enough stories to meet deadlines. This did mean that an air of

“we don’t want it good, we want it Tuesday” was sometimes evident.

Not every story – and there must have been thousands of them – was

ever likely to warrant being considered a work-of-art, or destined

to last beyond the week.

A case in point might be Elizabeth Burgoyne Corbett’s “Madame

Duchesne’s Garden Party”, which features a female sleuth named Dora

Bell. I think Rennison’s own summing up of this story might be

useful in explaining why he considered it worthy of inclusion: “The

Dora Bell stories are short and uncomplicated, ideally suited to the

newspaper readership at which they were aimed. They win no prizes

for great originality, but they remain entertaining and

easy-to-read”. Some of the attraction for readers probably arose

from the stories often being built around a particular detective.

There were, It seems, several Dora Bell tales, though they don’t

seem to have ever been published in book form after they’d graced

the pages of the Leeds

Mercury and The Adelaide

Observer.

I’ve remarked elsewhere that the lives of the authors often seem as

interesting as the stories they wrote, and Corbett (1846-1930)

produced novels, one of which uses the basic theme of someone

falling asleep and waking up in a different century. Corbett

imagined a world where women are in control and lifespan has been

extended to around five hundred years. Society is “fairer and less

corrupt”, but a form of eugenics is practised. It was a subject in

the air in the late-Victorian and Edwardian periods and aroused the

curiosity of some prominent writers, and not just those who

published what might be called fiction for the masses. I have to

admit that the title of one of Corbett’s crime novels, “When the Sea

Gives Up its Dead” is almost enough to make me start searching for a

copy. But would I be disappointed if I read it?

I’d read Clarence Rook’s “The Stir Outside the Café Royal” before

picking up Sherlock’s Sisters

(it’s in Crime on Her

Mind, edited by Michele B. Slung, Penguin, 1977), and it’s

another story that is best described as routine. The interest might

lie in its brief portrait of the scene around the entrance to the

Café Royal. Rook (1862-1915) is remembered, if he is, for his book,

The Hooligan Nights,

which purported to be the authentic story of a young tearaway from

Lambeth. Rennison suggests that Rook may not have strayed too far

from his study when researching for his book, and that it might have

been more than influenced by Arthur Morrison’s

Tales of Mean Streets.

Mentioning Rook indicates that, although the stories have female

detectives at their centre, not all of them were written by women.

George R. Sims (1847-1922) created Dorcas Dene who solves the riddle

of “The Haverstock Hill Murder”. Sims – “a journalist, novelist,

dramatist and bohemian man-about-town” –

was a prolific author, one

of his creations being the poem, “Christmas Day in the Workhouse”.

It’s often parodied (the wonderful Billy Bennett did a

military-based version, “Christmas Day in the Cookhouse”, available

on YouTube), but as Rennison makes clear, it was originally designed

as “a biting critique of the Victorian poor laws”. There were twenty

Dorcas Dene stories, according to Rennison, and they were pulled

together in two volumes. They are now collectors’ items and when I

checked the available copies were priced at just over £5,000 for the

two.

I first encountered “The Redhill Sisterhood” by Catherine Louisa

Pirkis (1839-1910) when Hugh Greene included it in

Further Rivals of Sherlock

Holmes (Penguin, 1976), but it was worth reading again. It

features Loveday Brooke, one of the “most interesting and appealing

of late Victorian female detectives”, who manages to operate

successfully in a world largely dominated by men. She doesn’t resent

them and has an eye for a good-looking chap. The story is intriguing

for its period details and starts in London on a “dreary November

morning, every gas jet in the Lynch Court office was alight, and a

yellow curtain of outside fog draped its narrow windows”.

When Brooke is despatched to investigate some shady dealings they

are in an area “known to the sanitary authorities for the past ten

years as a regular fever nest”. Later, there are references to the

introduction of electric lighting in more-prosperous locations, and

its supposed effectiveness in deterring burglars “If electric

lighting were generally in vogue it would save the police a lot of

trouble on these dark winter nights”. At one point a policeman says

of someone, “he has weathered me, after all”, presumably meaning

that the man has spotted and/or recognised him. I can’t recall ever

seeing “weathered” used in this way before.

It’s also possible to get a picture of Victorian life from a passage

in Fergus Hume’s “The Fifth Customer and the Copper Key” when the

detective, Hagar the Gypsy, enters a room “furnished in the ugly

fashion of the early Victorian era……..Chairs and sofa were of

mahogany and horsehair; a round table, with gilt-edged books lying

thereon at regular intervals, occupied the centre of the apartment,

and the gilt-framed mirror over the fireplace was swathed in green

gauze. Copperplate prints of the Queen and the Prince Consort

decorated the crudely-papered walls, and the well-worn carpet was of

a dark green hue sprinkled with bouquets of red flowers”.

Hume (1859-19320) was the author of

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab,

said by Rennison to be “the most popular novel of the Victorian

era”. He published it himself in Australia, when he lived there, and

then sold the English rights for £50. When it became a best-seller

he didn’t profit from it. But he went on to publish over 150 novels

and collections of short stories.

I was intrigued by the occurrence of narcotics in a couple of the

stories, and Madelyn Mack, the “most flamboyant and eccentric female

detective”, was created by Hugh Cosgrove Weir (1884-1934) for “The

Man with Nine Lives”. She chews cola berries as a stimulant when

needing to consider the facts of a case. And the victim of a murder

she’s looking into turns out to have been addicted to “Indian hemp

or ‘hasheesh’ for some time”. The murderer finds a particularly

clever way of ensuring that the man imbibes a lethal dose of the

drug. Amusingly, this story really is one where “the butler did it”.

“The Dope Fiends” by Arthur B. Reeve (1880-1936) has Constance

Dunlap tracking down a cooked doctor, a shady pharmacist, and a bent

policeman engaged in supplying cocaine to, among others, members of

the theatrical profession.. My thoughts were drawn back to Billy

Bennett again. He had an amusing monologue about his mother being so

worried that’s he may become a performer on stage that she gladly

accepts his assurance that the powder on the shoulders of his suit

is only cocaine and not make-up. But

Reeves’s heroine has a more-serious purpose in mind and it is to

save a young dancer from the grip of the drug. Reeve worked as

journalist, a consultant in crime-prevention, and wrote serials for

the early American cinema. I was curious about the date of his story

and whether or not it fell strictly within the Victorian/Edwardian

category. It seems to have been in a collection of his stories

dating from 1916, but may have been published earlier in a magazine.

But perhaps I’m niggling?

Another American writer, Anna Katharine Green (1846-1935)

highlighted Violet Strange as the focus of some of her short

stories. Strange was a rich man’s daughter and didn’t need to work,

but liked to carry out investigations on behalf of a New York

private detective agency. She doesn’t care to take on murder cases,

but gets involved in one involving an elderly lady in a house,

described as “of the olden times……it has a fanlight over the front

door………and two old-fashioned strips of parti-coloured glass on

either side…….and a knocker between its panels which may bring money

some day”. The story has a somewhat contrived ending, but Rennison

aptly sums it up as “well-written and entertaining”.

Green’s work included The

Leavenworth Case, an 1878 novel said to be one of the earliest

of all American detective novels. She wrote other novels which

featured an investigator called Ebenezer Gryce, “one of the first

series characters in detective fiction”.

One of the most intriguing and well-written stories in

Sherlock’s Sisters is

“The Long Arm” by Mary E.Wilkins (1852-1930). Rennison points out

that Wilkins was not a crime writer and the woman at the centre of

her story is not a detective in the accepted sense of the word. She

is, instead, Sarah Fairbanks, a country schoolteacher twenty-nine

years of age, who has been engaged for five years to a young man.

But her father opposes the match. When he is murdered suspicion

naturally falls on both her and her fiancé. He has an alibi to prove

that he was elsewhere at the time of the murder, but she is arrested

and charged. She is acquitted, but suspicion lingers, and she

determines to discover the real killer. The story-telling does have

some originality and flair, and if the ending is a little

melodramatic the overall impression is effective.

Wilkins wrote stories based in New England and involving

“marginalised characters struggling with the frustrations and

constraints of their lives”.

But Rennison says that although they “won her much praise” at

the time of their publication, “today she is probably better known

for her stories of ghosts and the supernatural”. I have to say I

looked in vain for a reference to her in Malcolm Cowley’s

New England Writers and

Writing (University Press of New England, 1996), though I was

perhaps expecting too much in thinking she might be there. Larzer

Ziff does devote a few pages to her New England stories in

The American 1890s: The Life

and Times of a Lost Generation (Chatto & Windus, 1966).

There are other stories that are worthy of mention. “The Episode of

the Needle that did not Match” by Grant Allen (1848-1899), has Hilda

Wade exposing how ambition can overcome scruples, and professions

are sometimes too willing to overlook the faults of the famous.

Allen is yet another popular writer who is now almost forgotten.

Likewise with Richard Marsh (1857-1915) whose “Eavesdropping at

Interlaken” gives us Judith Lee, a young lady with an uncanny gift

for lip-reading, even at a distance. It serves her in good stead

when she is accused of stealing jewellery in a hotel where she is

staying, and she is able to unmask the real thieves. I suppose there

has to be a degree of suspending disbelief when reading a story like

this – can she really be that gifted? – but it rolls along easily

and it’s not hard to enjoy its light entertainment .

Sherlock’s Sisters

is another excellent anthology from Nick Rennison. If one or two of

the stories creak a little it’s still possible to consider them of

some value, even if only for their period charm. And sometimes they

offer insights into how

words change their meaning or application as the years pass. A young

man says he “whipped down the stairs” (meaning dashed down), in the

Loveday Brooke story, and it’s not something I’ve heard recently,

though I would have said it myself seventy and more years ago. But

I’m sure someone will soon tell me that it’s still in use. And some

readers might want to identify with an old lady in the Baroness

Orczy (1865-1947) Lady Molly of Scotland Yard story, “the Woman in

the Big Hat”, who says, “I hate all this modern smartness and

fastness, which are only other words for what I call profligacy”.

Somehow its relevance doesn’t really sound all that old.

|