|

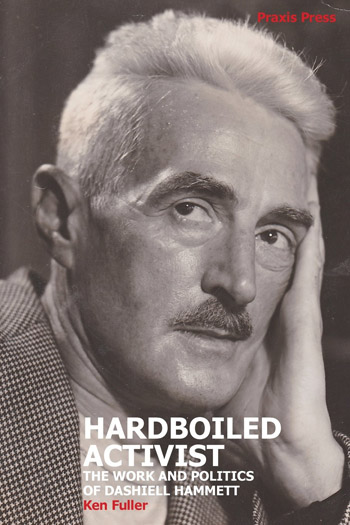

HARDBOILED ACTIVIST: THE WORK AND POLITICS OF DASHIELL HAMMETT

BY Ken Fuller

Praxis Press. 334 pages. £19.99/$25. ISBN 978-1-899155-06-4

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Dashiell Hammett is probably best known as the author of

The Maltese Falcon, a

novel that was also made into a classic film starring Humphrey

Bogart as the hard-boiled private detective, Sam Spade. Hammett

wrote four other novels, and dozens of short stories of variable

quality, though you may need to be an enthusiast for tough-guy

writers from the 1930s and 1940s to want to read them all. Pulp

fiction, even at its best, had limitations and often suffered from

the need for quick productions that wouldn’t make too many demands

on its readers. I say that as an avid reader of pulp writers, and

they sometimes surprise when the quality of their writing moves

beyond the merely functional and turns into literature. But a lot of

it is less than good, and there’s little to be gained by pretending

otherwise.

Hammett is more interesting than many of the writers of pulp novels

and stories. Prior to writing he had served in the American army at

the time of the First World War, and had worked as a Pinkerton

detective. From the point of view of his later political

involvements, his Pinkerton period included strikebreaking, the

agency having a notorious reputation for that kind of activity. Just

how far he went in terms of any sort of physical contact with

strikers is impossible to know. He may just have been behind the

scenes, organising the roughnecks who broke up picket lines and

terrorised strikers’ families. He was always a little vague about

what he had actually done.

His long-time partner, the playwright Lillian Hellman, said that

Hammett once told her that he’d been offered $5,000 to murder the

IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) organiser, Frank Little,

during a strike in Butte, Montana, but as both Hammett and Hellman

were unreliable when it came to facts, it’s best to discount this

story. Frank Little was murdered in 1917, in a particularly nasty

way, but by vigilantes. There is a gloating fictionalised version of

his lynching in Zane Grey’s rabble-rousing novel,

When Hammett moved on from his Pinkerton employment he had a family

to support and turned to writing to make money. The

Because of the early anti-labour activities, and his later

commitment to the Communist Party, some critics and commentators

have looked for signs of radical leanings in Hammett’s fiction. Ken

Fuller says there are none, and I’m inclined to agree with him. As

he rightly points out, it is possible to conclude that Hammett was

anti-capitalist, but that isn’t the same as being a socialist or

communist. He had more of a nihilistic attitude towards life, and

seemed to take the view that working for the Pinkerton Agency, was

simply a job to be done as efficiently as possible, no matter what

it involved. There is a brief appearance by an IWW organiser in the

novel, Red Harvest, but

he soon disappears from the story and has no significance in the

plot.

Hammett wrote five published novels and, as mentioned earlier, many

short stories, most of which appeared in the famous pulp magazine,

Black Mask. The novels

were serialised in the same publication, and the padding out, and

obvious signs of hasty writing, that is sometimes in evidence

probably came about because he was paid by the word, so he wrote to

earn a bigger cheque. He certainly was never determined to make a

political point in his novels and stories in the way that

proletarian writers did in the 1930s. One of his most popular

creations was the partnership of Nick and Nora in

The

Thin Man, which after its

initial success as a book and film led to a short series of

cinematic adaptations, thus putting extra money into Hammett’s

account.

The portrayal of hard-drinking, wise-cracking socialites (based in

part on Hellman and himself?) may have appeared odd to anyone who

knew of Hammett’s developing political leanings. But, then again,

perhaps not. No-one really expected pulp writers, or anyone

connected with

Fuller quotes someone else as saying: “The moral vision of

The Thin Man is dark

indeed”. And he adds that “Nick Charles has no social conscience,

surrounding himself with riches and numbing himself with alcohol at

a time when 15 million American are unemployed”. Is this Hammett

shining a light on the indifference to suffering of the rich, or

perhaps looking at himself and finding his own actions questionable?

The latter interpretation could be nearer the truth. He earned good

money, but squandered it on drink and prostitutes.

When did Hammett become politicised? Some have suggested that it was

around 1930, when he started his relationship with Hellmann, but a

likelier time was a little later. The rise of the Popular Front

policy, the start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and Hammett’s

presence in

Why did Hammett, a cynical, worldly-wise man whose philosophy of

life tended towards nihilism, if anything, join the Communist Party

and often adhere to its policies even when other people were

questioning them? He agreed with the Party line about

Hammett’s drinking was always a problem, though he did have long

periods on the wagon. It’s interesting that, assuming he was a

member, the Party seems to have turned a blind eye to what Fuller

describes as the “strong bohemian strain in the behaviour of Hammett

and Hellman”. Both drank, Hammett obviously more than she did, and

had various affairs which they didn’t try to keep quiet about. Were

their misdemeanours accepted because they were high-profile people

who, particularly during the Popular Front period and the Second

World War, the Party found it useful to have around for publicity

purposes? And what do we know, if anything, about how much they

contributed to Party funds. One of the reasons the Party cultivated

connections with writers and others in

Hammett served in the army during the Second World War, and on his

return to the

Never a really well-man from a health point of view, Hammett had

suffered from tuberculosis and the years of heavy drinking had also

taken their toll. He refused to take things easier, but was

eventually hospitalised and died of lung cancer in 1961.

It’s easy to see why Hammett had a reputation for being

“hardboiled”. His intransigence when it came to supporting the Party

line, and his lack of sentiment about the working-class, set him

apart from many idealistic middle-class communists and

fellow-travellers. He didn’t expect people from working-class

backgrounds to be any better than they were. Fuller refers to a

short story called “The Hunter,” in which a private detective beats

up a man who has been forging cheques in order to make him confess.

He doesn’t think about why the man committed the crime (he has

domestic problems and a family to support). It’s simply his job to

get a confession and hand him over to the police. Fuller says that

it’s a “stark illustration of what one working man will do to

another due to their respective roles within the capitalist system”.

I suspect that, deep down, Hammett may not have thought that people

would ever be any different in their habits and prejudices, even

under a communist system.

Ken Fuller has done a good job with looking at Hammett’s work,

analysing the novels in detail, and surveying some of the short

stories. He’s also taken into account Hammett’s short-lived and not

very successful career as a writer in

Hammett’s sometimes-violent relationship with Lillian Hellman is

also dealt with, and his possible contributions to the plays she

wrote. As mentioned earlier, she wasn’t the most reliable of

witnesses and the fact that she outlived him by many years (she died

in 1984) meant that she could, in a sense, re-write the past in

interviews and her autobiographical publications. She famously fell

out with many people, and just before she died was about to take on

Mary McCarthy in court. McCarthy had said that every word Hellman

wrote was “a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the’ “. It was, essentially,

a continuation of an argument that went back in

Hardboiled Activist

is a lively read and Ken Fuller is obviously a devotee of Hammett’s

fiction. He also has a sympathetic take on his political convictions

and, in his way, attempts to justify Hammett’s support for the

purges in

|