|

ARTIST

QUARTER: MODIGLIANI, MONTMARTRE & MONTPARNASSE

By Charles Douglas

Pallas Athene (Publishers) Ltd.

353 pages. £14.99. ISBN 978-1-84368-153-3

Reviewed by Jim Burns

It’s useful to spend a little time looking at the origins of this

book. It was first published by Faber in 1941, and the author’s

name, Charles Douglas, was made up from the names of the two writers

involved, Charles Beadle and Douglas Goldring. The latter may be

reasonably-familiar to anyone interested in English literature in

the period between the two World Wars. He was a prolific novelist,

poet, and critic, and his memoir,

The Nineteen Twenties, is

still worth reading.

But who was Charles Beadle? There isn’t a lot of easily-available

information about him, and I’m indebted to Neil Pearson’s scholarly

Obelisk: Jack Kahane and the

Obelisk Press (Liverpool University Press, 2007) for the details

I’m listing here. Beadle was born “around

A third, Dark Refuge

(1938), could only have come from the Obelisk Press. Pearson says:

“In earlier books Beadle denounced the Paris-based expatriates for a

bohemianism he deemed so insipid as to scarcely merit the name. In

Dark Refuge he spells out

how it should be done properly, and does so without paying any heed

to what was considered publishable at the time. Beadle’s ticket to

the dark side is opium, and in his world ‘dark’ has no negative

connotations, but refers instead to the side of the self that sees

too little llght”. Mix that with what appears to be an open approach

to matters of sex, and the language to describe it, and no publisher

in

It is difficult to work out exactly who wrote what in

Artist Quarter. Goldring

had lived in

Anecdotes are at the core of

Artist Quarter, many of them about Modigliani, but most of them

generally highlighting the activities of the artistically inclined

but often impecunious. Utrillo is seen in his usual alcoholic haze,

avoided by others in the bohemian community because of his behaviour

when drunk. He wasn’t a happy drunk, likely to lapse into silence or

even sleep, but instead tended to shout, break glasses, and

generally misbehave. Utrillo’s paintings of

Picasso was, of course, very much a notable figure in Montmartre in

the pre-1914 period, living at the Bateau-Lavoir, a tumble-down

building which served as a gathering-place for painters and poets,

such as André Salmon, Kees Van Dongen, Vlaminck, Derain, Max Jacob,

Apollinaire, and associated models and mistresses.

Fernande Olivier was with Picasso in those days, and “he was

so jealous of her that he would not let her go out, but trotted out

himself with the market bag every morning to the rue de Abbesses,

just below the studio, to buy the day’s supplies”. A view of

Picasso’s studio refers to it as “dirty, curtainless, and in

disorder. Unfinished canvases are propped against the dusty

walls……..A towel and a bit of yellow soap lie on a table among tubes

of paint, brushes, and a dirty plate containing remnants of a hasty

meal……On the floor there is another litter of paints, brushes,

bottles of paraffin”. It’s a colourful description and perhaps

intended to confirm everyone’s suspicions regarding how bohemians

lived.

It was during this period of Picasso’s career that he painted a

portrait of one of the

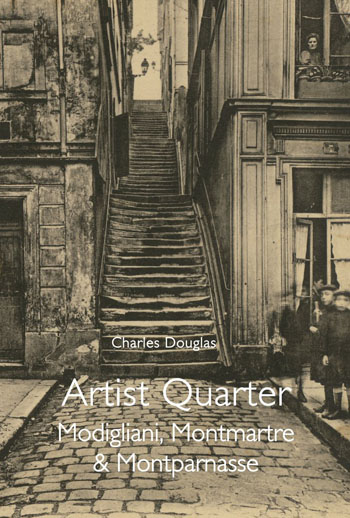

I was intrigued to see that, on the opposite page to the notes about

Picasso’s studio, there is an

illustration of the Passage Cottin in

According to the account in

Artist Quarter, the poet and painter Max Jacob lived by a form

of voluntary poverty. Beadle, or was it Goldring, once told a

gallery owner that Jacob, then domiciled in the provinces, was still

poor, to which she replied, “Oh, that’s only because he wants to

be”. When he lived in

the Bateau-Lavoir, Jacob got high on ether, as did others, including

Modigliani, at least until opium became easily available. Jacob, a

Jew, was arrested in 1944 and died in the

The Polish poet, Leopold Zborowski, sacrificed a great deal of his

time, energy, and money, trying to help Modigliani, though he was

often abused and exploited by the artist, and when Modiglani died he

was accused of profiting from the sale of some of his paintings that

he had. But it’s documented how dealers descended on anyone who had

a Modigliani work in their possession and bought and resold them for

ever-increasing prices. It took Modigliani’s death, and that of his

last female companion, the ill-fated Jeanne Hébuterne, to bring him

the fame he never had in his lifetime. Their story became the basis

for novels and films, and any number of supposedly-factual accounts.

Modigliani had several affairs, one of them with a woman the book

refers to as “The English Poetess”, presumably because the person

concerned was still alive in 1941 and wouldn’t have wanted her name

made public. It’s now known that she was Beatrice Hastings. Their

intense but tumultuous relationship lasted for around two years

before she brought it to an end. She eventually returned to

The English artist Nina Hamnett also knew Modigliani in the years

before the First World War and seems to have liked him. Reminiscing

about her time in

Artist Quarter

is full of the names of painters and poets who failed to survive the

bohemian scene. The artist Jules Pascin “destroyed himself at the

height of his fame, when his work was in great demand and he had no

financial worries. Perhaps that was a reason for his suicide: he was

surfeited with success, physically worn out with years of riotous

living, and life had nothing more to offer him”. And there was the

poet, Ralph Cheever Dunning, who was published in expatriate

magazines like Ford Madox Ford’s

The Transatlantic Review

and Ezra Pound’s The Exile.

Pound was an advocate for his poetry, though it’s difficult now to

know why. It must have seemed old-fashioned even then, especially

when Pound’s clarion call, “Make it New”, could still be heard.

Dunning was an opium addict and died of tuberculosis and starvation

in

Beadle and Goldring don’t have much to say about the influx of

Americans in the 1920s, though they do mention Harold Stearns, an

intellectual who wrote a book called

America and the Young

Intellectuals and edited another called

Civilisation in the United

States, and then went to Paris, where in “Montparnasse the

‘antilectual’ toxin took so well that he became ‘Peter Pickem’ for

the Chicago Tribune – and

afterwards the Paris Daily

Mail – and for years, from the top of a stool in The Select,

picked winners with uncanny accuracy”. Kay Boyle’s 1938 novel,

Monday Night, features a

character closely based on Stearns.

There is so much packed into the pages of

Artist Quarter that it’s

impossible to mention all the painters, writers, and others who were

around Montmartre or

|